$35.49 Buy It Now or Best Offer

free,30-Day Returns

Seller Store ancientgifts

(5343) 100.0%,

Location: Ferndale, Washington

Ships to: US,

Item: 126676729425

Restocking Fee:No

Return shipping will be paid by:Buyer

All returns accepted:Returns Accepted

Item must be returned within:30 Days

Refund will be given as:Money back or replacement (buyer’s choice)

Format:Oversized softcover

Length:48 pages

Dimensions:8¼ x 5¾ inches

Publisher:British Museum (2005)

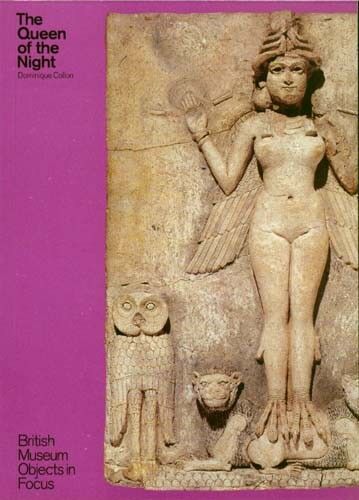

“The Queen of the Night” by Dominique Collon. NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title. DESCRIPTION: Softcover. Publisher: British Museum (2005). Pages: 48. Size: 8¼ x 5¾ inches. Summary: This large Old Babylonian plaque, found in southern Iraq, was made between 1800 and 1750 B.C. It is made of baked straw-tempered clay, modeled in high relief, and probably stood in a shrine. The figure could be an aspect of the goddess Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sexual love and war; or Ishtar’s sister and rival, the goddess Ereshkigal who ruled over the Underworld; or the demoness Lilitu, known in the Bible as Lilith. This book explores the symbolism and history behind this beautiful relief. The figure wears the horned headdress characteristic of a Mesopotamian deity and holds a rod and ring of justice, symbols of her divinity. Her long multi-colored wings hang downwards, indicating that she is a goddess of the Underworld. Her legs end in the talons of a bird of prey, similar to those of the two owls that flank her. The background was originally painted black, suggesting that she was associated with the night. She stands on the backs of two lions, and a scale pattern indicates mountains. The relief may have come to England as early as 1924, and was brought to the British Museum in 1933 for scientific testing. The relief was in private hands until its acquisition by the Museum in 2003. CONDITION: NEW. New oversized softcover. British Museum (2005) 48 pages. Unblemished, unmarked, pristine in every respect. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 14 days! #9170a. PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK. PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW. PUBLISHER REVIEWS: REVIEW: A concise and beautifully designed book exploring the symbolism behind an exquisite Ancient Babylonian plaque found in southern Iraq. This spectacular terracotta plaque was the principal acquisition for the British Museum’s 250th anniversary, and in 2004 was exhibited in various museums around the U.K. Made between 1800 and 1859 B.C., it is made from baked straw-tempered clay and modeled in high relief. It probably stood in a shrine and could represent the demoness Lilitu, known in the Bible as Lilith, or a Mesopotamian goddess. The figure wears the horned headdress characteristic of a Mesopotamian deity, and holds a rod and ring of justice, symbols of her divinity. Her long multi-colored wings hang downwards, indicating that she is a goddess of the Underworld. The book explores the history and symbolism behind this beautiful and highly unusual relief. REVIEW: Burney Relief/Queen of the Night. Rectangular, fired clay relief panel; modelled in relief on the front depicting a nude female figure with tapering feathered wings and talons, standing with her legs together; shown full frontal, wearing a headdress consisting of four pairs of horns topped by a disc; wearing an elaborate necklace and bracelets on each wrist; holding her hands to the level of her shoulders with a rod and ring in each; figure supported by a pair of addorsed lions above a scale-pattern representing mountains or hilly ground, and flanked by a pair of standing owls; fired clay, heavily tempered with chaff or other organic matter; highlighted with red and black pigment and possibly white gypsum; flat back; repaired. Scientific analysis of the pigments reveals extensive use of red ochre on the body of the main female figure. It is probable that gypsum was used as a white pigment in some areas although the possibility that it is present as the result of efflorescence from salts contained in ground water cannot be firmly excluded. The dark areas on the background all contained carbon rather than bitumen as previously assumed. The shape and basic composition of a large central figure flanked by a pair of small figures is reminiscent of a gypsum plaque attributed an early second millennium B.C. and found at Assur in 1910. Other evidence for early 2nd mill. painted clay sculptures from Mesopotamia include a head in the National Museum in Copenhagen. A similar motif occurs on terracotta plaques for which a mould also survives. This motif, curiously, also recurs on reproduction Roman terracotta lamps sold in western Turkey (of which there is one example in the registered ANE Ephemera collection) as well as in popular modern western cults. The term “Queen of the Night” has also been previously applied to a character in Mozart’s “Magic Flute” [“Die Zauberflote”], for which David Hockney did Egyptianizing sets for in the 1978 Glyndebourne production; features in a song by Whitney Houston, and is the name of at least one species of night-blooming orchid cactus, the Epiphyllum oxypetallum. Mr. Sakamoto added a Japanese inscription and the date 1975 onto the bottom edge of the object when it was in his personal possession. [British Museum]. REVIEW: This large Old Babylonian plaque, found in southern Iraq, was made between 1800 and 1750 BC. It is made of baked straw-tempered clay, modeled in high relief, and probably stood in a shrine. This book explores the symbolism and history behind this beautiful relief. REVIEW: Dominique Collon is an Assistant Keeper in the Department of the Ancient Near East at the British Museum. She is the author of “Ancient Near Eastern Art”, “First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East”, “Interpreting the Past: Near Eastern Seals”, and two catalogues of the cylinder seals in the British Museum’s collection. REVIEW: Dominique Collon is curator of the Mesopotamian collections in the British Museum. TABLE OF CONTENTS: Maps. 1. From “Burney Relief” to “Queen of the Knight”. 2. Creating the “Queen of the Night”. 3. The “Queen of the Night” and her Attendants. 4. Who was the “Queen of the Night”? Further Reading. Photographic Credits. PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS: REVIEW: A large Old Babylonian plaque was found in Iraq. This book explores the symbolism and history behind this beautiful relief. The figure wears the horned headdress characteristic of a Mesopotamian deity and holds a rod and ring of justice, symbols of her divinity. Her legs end in the talons of a bird of prey and she stands on the backs of two lions. Highly recommended. Compact, erudite text, stunning photography. [The Telegraph (UK)]. REVIEW: Who is this lady? The answers are to be found in this exceptional and amply illustrated little book. [ArtNewsletter.com]. READER REVIEWS: REVIEW: This book is part of a series of short guides produced by the British Museum. It is very informative, though final identification of the winged and bird-footed goddess proved inconclusive. The main contenders were Ištar, Lilith and Erishkigal. The photos are excellent and the color reconstruction of the plaque is truly striking. My own belief is that the figure in the relief is a divine lilu. They were renown for visiting men and women in the night and making love to them. Their love-making could, it seems, lead to children, as the Sumerian King List actually states that a lilu demon was the father of Gilgamesh. REVIEW: The series of books of which this is a part are fabulous. The British Museum certainly knows its customers. An interesting focus on just one item in the museum. And there are many more that cover the most interesting pieces in the museum. A well written booklet about “The Queen of the Night” with archaeological and historical information, as well as great illustrations. REVIEW: A good short guide to the Queen of the Night. It is a booklet, not a full-length book. With that in mind, the information is very good and the pictures are of excellent quality. ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND: REVIEW: The Queen of the Night (also known as the Burney Relief) is a high relief terracotta plaque of baked clay, measuring 19.4 inches (49.5 cm) high, 14.5 inches (37 cm) wide, with a thickness of 1.8 inches (4.8 cm) depicting a naked winged woman flanked by owls and standing on the backs of two lions. It originated in southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) most probably in Babylonia, during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) as it shares qualities in craftsmanship and technique with the famous diorite stele of Hammurabi’s laws and also with the piece known as ‘The god of Ur’ from that same period. The woman depicted is acknowledged to be a goddess as she wears the horned headdress of a deity and holds the sacred rod-and-ring symbol in her raised hands. Who the winged woman is, however, has not been agreed upon, though scholars generally believe her to be either Inanna (Ishtar), Lilith, or Ereshkigal. [The British Museum]. REVIEW: The Queen of the Night (also known as the Burney Relief) was a major acquisition for the British Museum’s 250th anniversary. This large plaque is made of baked straw-tempered clay, modeled in high relief. The figure of the curvaceous naked woman was originally painted red. She wears the horned headdress characteristic of a Mesopotamian deity and holds a rod and ring of justice, symbols of her divinity. Her long multi-colored wings hang downwards, indicating that she is a goddess of the Underworld. Her legs end in the talons of a bird of prey, similar to those of the two owls that flank her. The background was originally painted black, suggesting that she was associated with the night. She stands on the backs of two lions, and a scale pattern indicates mountains. The figure could be an aspect of the goddess Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sexual love and war, or Ishtar’s sister and rival, the goddess Ereshkigal who ruled over the Underworld, or the demoness Lilitu, known in the Bible as Lilith. The plaque probably stood in a shrine. The same goddess appears on small, crude, mould-made plaques from Babylonia from about 1850 to 1750 BC. Thermoluminescence tests confirm that the ‘Queen of the Night’ relief was made between 1765 and 45 B.C. The relief may have come to England as early as 1924, and was brought to the British Museum in 1933 for scientific testing. It has been known since its publication in 1936 in the Illustrated London News as the “Burney Relief”, after its owner at that time. Until 2003 it has been in private hands. The Director and Trustees of the British Museum decided to make this spectacular terracotta plaque the principal acquisition for the British Museum’s 250th anniversary. [The British Museum]. REVIEW: The Queen of the Night (also known as the `Burney Relief’) is a high relief terracotta plaque of baked clay, measuring 19.4 inches (49.5 cm) high, 14.5 inches (37 cm) wide, with a thickness of 1.8 inches (4.8 cm) depicting a naked winged woman flanked by owls and standing on the backs of two lions. It originated in southern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) most probably in Babylonia, during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) as it shares qualities in craftsmanship and technique with the famous diorite stele of Hammurabi’s laws and also with the piece known as `The god of Ur’ from that same period. The woman depicted in the relief is acknowledged to be a goddess as she wears the horned headdress of a deity and holds the sacred rod-and-ring symbol in her raised hands. Not only is the woman winged but her legs taper to bird talons (which seem to grip the lion’s backs) and she is shown with a dew claw on her calves. Along the base of the plaque runs a motif which represents mountains, indicating high ground. Who the winged woman is, however, has not been agreed upon though scholars generally believe her to be either Inanna (Ishtar), Lilith, or Ereshkigal. The piece is presently part of the collection of the British Museum, Room 56, in London. In 1936 A.D. the Burney Relief was featured in the Illustrated London News highlighting the collection of one Sydney Burney who purchased the plaque after the British Museum passed on the offer to buy it. Since the piece was not archaeologically excavated, but rather simply removed from Iraq sometime between the 1920’s and 1930’s, its origin and context are unknown. How the plaque arrived in London is also unknown, but it was in the possession of a Syrian antiquities dealer before coming to the attention of Sydney Burney. Not much is known of Sydney Burney other than that he was a Captain in the English Army during World War I and was President of the Antique Dealers Association in London. The plaque was broken in three pieces and some fragments when originally purchased but, once repaired, was found to be mostly intact. The Burney Relief was analyzed in 1933 and authenticated in 1935 prior to the offer made to the British Museum. The plaque then changed hands twice before the British Museum finally acquired it in 2003 for the sum of 1,500,000 pounds, a considerably higher price than what was asked in 1935. It was at this time that the piece known as the Burney Relief came to be called `The Queen of the Night’ due to the dark black pigment of the plaque’s original background and the iconography (the downward pointing wings, the talon feet etc.) associating the female figure with the underworld. The name is therefore a modern, not an ancient, designation for the plaque. There is no way to know what the piece was originally called or what purpose it was created for. The relief was made of clay with chaff added to bind the material and prevent cracking. The fact that the piece was fired in an oven, and not sun dried, testifies to its importance as only the most significant works of art and architecture were created in this way. Since timber was scarce in southern Mesopotamia, it was not used lightly for firing clay objects. According to Dr. Dominique Collon of the British Museum the plaque was made by: “…clay pressed into a mould and allowed to dry in the sun…the figure was made from fairly stiff clay which was folded and pushed into a specially shaped mould, with more clay added and pressed in behind to form the plaque. Thus the Queen’s figure is an integral part of the plaque and was not added to it later. ” “After drying, the plaque was removed from the mold, the details were carved into the leather-hard clay and the surface was smoothed. This smoothed surface is still visible in certain places, notably near the Queen’s navel…The edges of the plaque were trimmed with a knife. Then the plaque was baked.” Once the piece was done baking and had cooled, it was painted with a black background, the woman and the owls in red, and lions in white with black manes. The rod-and-ring symbols, the woman’s necklace, and her headdress were gold. The original color traces may still be detected on the piece today even though they have largely worn away over the centuries. While it may never be known exactly where the piece was made, for what purpose, or which goddess it represents, the similarities in technique between it and the so-called `God of Ur’, are so striking that it has been speculated that the Sumerian city of Ur is its place of origin. Dr. Collon notes: “The god from Ur is so close the Queen of the Night in quality, workmanship and iconographical details that it could well have come from the same workshop, perhaps at Ur, where extensive remains of the Old Babylonian period were excavated between 1922 and 1934. The individual who originally removed the plaque, then, could have been a member of one of the excavating teams during that time or simply someone who came upon the piece once it was uncovered. Theories as to its original placement and significance have been suggested by every scholar who has studied it. As sacred prostitution was practiced throughout Mesopotamia, the historian Thorkild Jacobsen believed that the plaque formed a part of a shrine in a brothel. Dr. Collon notes, however, that “if this were so, it must have been a very high-class establishment, as demonstrated by the exceptional quality of the piece”. She further theorizes that the plaque would have been hung on a wall of mud brick, probably in an enclosure, and that, when the mud brick wall collapsed, the fired terracotta plaque would have remained relatively intact. The fact that the piece has survived for over 3000 years attests to its having been buried fairly early after the building which housed it fell or was abandoned because it was thereby protected from the elements and from vandalism. The identity of the Queen is the most intriguing aspect of the piece and, as noted above, three candidates have been proposed: Inanna, Lilith, and Ereshkigal. The nude woman motif was popular throughout Mesopotamia. The historian Jeremy Black notes: “Hand-made clay figurines of nude females appear in Mesopotamia in prehistoric times; they have applied and painted features. Figurines of nude women impressed from a pottery or stone mould first appear at the beginning of the second millennium BC…It is very unlikely that they represent a universal mother goddess, although they may have been intended to promote fertility.” Inanna would be the goddess in keeping with a plaque encouraging fertility as she presided over love and sex (and also war) but there are a number of problems with this identification. If one accepts the findings of Dr. Black and others who agree with him, then that poses a problem with Inanna as Queen of the Night since she was not universally regarded as a mother goddess in the way that Ninhursag (also known as Ninhursaga) was. Ninhursag was the mother of the gods and was regarded by the people as the great mother goddess. There are also problems with Inanna as the Queen stemming from the iconography of the piece. While Inanna is associated with lions, she is not linked with owls. The headdress and the rod-and-ring symbols would fit with Inanna, as would the necklace, but not the wings or the talon-feet and dew claw. The scholar Thorkild Jacobsen, arguing for Inanna as the Queen, presents four aspects of the plaque which point to the Queen’s identity: 1) Lions are an attribute of Inanna. 2) The mountains beneath the lions are a reflection of the fact that Inanna’ s original home was on the mountaintops to the east of Mesopotamia. 3) Inanna took the rod-and-ring with her in her descent to the underworld and her necklace identified her as a harlot. 4) Her wings, bird talons and owls show that Inanna is pictured in her aspect of Owl goddess and goddess of harlots. Dr. Collon, however, dismisses these claims pointing out that Inanna “is associated with one lion, not two” and the point regarding the rod-and-ring symbol and necklace can be discounted as they “could have been worn or held by any goddess”. Dr. Collon also points out that the “first published photograph of the Queen of the Night relief in 1936 read: `Ishtar…the Sumerian goddess of love, whose supporting owls present a problem’”. Ishtar was the later name for Inanna and, while owls have been mentioned in tales concerning the goddess, they were never a part of her iconography. Further, Inanna is never depicted frontally in any ancient art but, always, in profile and the mountain range at the bottom of the plaque could argue as well for identification with Ereshkigal or Lilith. Lilith is a demon, not a goddess, and although there is some association of the Lilith demon with owls, they are not the same kind of owls that appear on the relief. Further, Lilith comes from the Hebrew tradition, not the Mesopotamian, and corresponds only to the Mesopotamian female demons known as lilitu. The lilitu and the so-called ardat lili demons were especially dangerous to men whom they would seduce and destroy. The male demons of this sort, the lilu, preyed on women and were an especial threat to those who were pregnant or had just given birth and also to infants. The article, “The Burney Relief: Inanna, Ishtar, or Lilith?” states why the Lilith identification is a probability. Rafael Patai (“The Hebrew Goddess” third edition) relates that in the Sumerian poem Gilgamesh and the Huluppu Tree, a she-demon named Lilith built her house in the Huluppu tree on the banks of the Euphrates before being routed by Gilgamesh. Patai then describes the Burney plaque: “A Babylonian terra-cotta relief, roughly contemporary with the above poem, shows in what form Lilith was believed to appear to human eyes. She is slender, well-shaped, beautiful and nude, with wings and owl-feet. She stands erect on two reclining lions which are turned away from each other and are flanked by owls. On her head she wears a cap embellished by several pairs of horns. In her hands she holds a ring and rod combination. Evidently this is no longer a lowly she-demon, but a goddess who tames wild beasts and, as shown by the owls on the reliefs, rules by night. Even so, the possibility that the Queen of the Night plaque, with its high degree of skill in craftsmanship and attention to detail would be a representation of a lilitu is highly unlikely. According to the Hebrew tradition, Lilith was the first woman made by God who refused to submit to Adam’s sexual demands and flew away, thus rebelling against God and his plans for human beings. She was thought to have then occupied the wastelands and, like the lilitu, to have preyed on unsuspecting men ever since. In either tradition, the lilitu was not a popular enough figure to have been portrayed on a plaque such as the Queen of the Night. Dr. Black notes, “Evil gods and demons are only very rarely depicted in art, perhaps because it was thought that their images might endanger people”. The mountain range depicted at the bottom of the relief is also thought to suggest lilitu identification in representing the wilderness the spirit inhabits but the headdress, the necklace, the rod-and-ring symbols and the significance of the plaque all go to argue against Lilith as a possibility. The third contender is Inanna’s older sister, Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Great Below. Her name means “Lady of the Great Place” referring to the land of the dead and there are a number of aspects of the plaque which seem to suggest Ereshkigal as the best candidate for Queen. The motif of the downward pointing wings was used throughout Mesopotamia to indicate a deity or spirit-being associated with the underworld and the Queen has such wings. Ereshkigal lived in the underworld palace of Ganzir, thought to be located in the eastern mountains, which would account for the mountain range depicted running along the bottom of the plaque. Regarding Ganzir and the underworld, Dr. Collon writes, “It was a dark place and the dead, naked or clothed with wings like birds, wandered with nothing to drink and only dust to eat. Whatever they had achieved in life, the only sentence was death, pronounced by Ereshkigal”. Ereshkigal is famously depicted in the poem Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld as naked: “No linen was spread over her body. Her breasts were uncovered. Her hair swirled around her head like leeks” (Wolkstein and Kramer, 65) and the Queen on the plaque is nude. Further, unlike depictions of Inanna in profile, the Queen is shown from the front. Dr. Collon writes: “As a goddess, Ereshkigal was entitled to the horned headdress and the rod-and-ring symbol. Her frontality is static and immutable and, as Queen of the Underworld where `fates were determined’, hers was the ultimate judgment: she might well have been entitled to two rod-and-ring symbols.” In this same way the lions the Queen stands on could represent Ereshkigal’ s supremacy over even the mightiest of living things and the owls, with their association with darkness, could be linked to the land of the dead. All of the iconography of the Queen of the Night plaque seems to indicate the deity represented is Ereshkigal but, as Dr. Collon states, “no definite connection with Ereshkigal can be made as she has no known iconography: her association with death made her an unpopular subject” (45). With no known iconography of Ereshkigal to compare the Queen of the Night with, the identity of the Queen remains a mystery. [Ancient History Encyclopedia] REVIEW: Room 56 of the British Museum; Mesopotamia: A large display case houses the “Queen of the Night Relief.” It is one of the masterpieces of the British Museum, also known as the “Burney Relief”. This terracotta plaque came from Mesopotamia (mostly modern-day Iraq) and dates back to the Old Babylonian period, 1800-1750 B.C. I stood a meter away from the case and watched the British Museum’s visitors; what will they do when they meet this “Queen?” Generally, they took some pictures of her and some selfies. A minute, more or less, they spent. It was my turn now. I approached the case; the glass was very clean and transparent. I will express my thoughts as a physician who examined the anatomical details of an approximately 4000 year-old woman. I’m a consultant neurologist, not an anatomist, but I studied anatomy in medical school. I scrutinized each and every centimeter of the Queen’s Relief and shot quite a few pictures. The female figure is portrayed as if she is alive; a very attractive and naked woman. The orbits (eye sockets) are hollow (might well have been inlaid with another material). The eyebrows are relatively thick and join each other at the mid-line; a style that is still used by many Iraqi women. The cheeks are full and her lips are thin and their corners are turned up (with a shy smile). The tips of her nose and chin are broken. The right external ear (or auricle) has survived, and its length spans the distance from the outer eye canthus (the outer angle where both eyelids meet each other) down to the corner of the mouth (perfect human anatomy). A close-up examination of the face of the female deity highlights the hollow eyes, full cheeks, and joined eyebrows. The upper left horn of her headdress and the left hair bun are lost. Part of her forehead is visible because she wears a four-tiered headdress of horns (symbol of divinity). The headdress is topped by a disc. The left upper horn is lost. The hair of the scalp is underneath the headdress. However, the bulk of her “long” hair is divided into two buns, on either side (the left one is lost). The rest of the hair is joined into two braids which extend down on either side of the upper chest wall and on a single broad necklace. What a versatile hairstyle she has! Part of the right half of the necklace is lost. The neck is relatively narrow and not that short. The shoulders are narrow and relatively down-sloping. The breasts are full and elevated and their outer margins extend beyond the outer (lateral) chest wall. There is no cleavage. Although there are no nipples, both areolae (the small pigmented circle around the nipple) were highlighted by a dark pigment. Both armpits are depicted clearly. The arms are symmetrically lifted up and the inner aspect of both hands face the viewer; the palm creases are very clearly demarcated. The thumbs are in an adducted position (adduct: to draw inward toward the median axis of the body or toward an adjacent part or limb) and hold a rod-and-ring symbol (the right one is lost), which is also a symbol of divine power. At both wrists there are bracelets of rings; traces of red color can still be seen at the base of the left thumb. Below the chest, the abdomen starts and it becomes narrow and its outer margins are concave. Then the pelvis is depicted wider than the mid-abdominal area; a very feminine attitude. The umbilicus (navel; belly button) is in its perfect anatomical position; it lies at the mid-point of an imaginary horizontal line, which joins the upper surface of both iliac crests (the upper outer margin of the boney pelvis). These boney crests are shown as convex curves on the outer margin of the upper pelvis. The pubic area is perfectly triangular in shape and curves inward. Both thighs are adducted very closely and meet at the midline. There is a small fusiform space between the inner aspects of both knee joints. We can find a patella (kneecap) at each knee joint. A short distance below the knee joints, small triangle protrusions stem off the lateral surface of both upper legs; they appear as dewclaws. At the ankles, the female’s feet become those of a bird. Each foot is composed of three equally long but separated toes. On the ankle and toes, we can find several scratches; these most likely represent scutes. The toes are fanned out and the feet rest on the backs of two lions that are flanked by two large owls. The queen has two wings. The wings are partially spread in a triangular shape. The wings are shown in a very well-demarcated and stylized register of feathers. Both wings extend from just above the shoulders down to the upper part of both thighs. The wings are very similar but they are not symmetrical; they differ in the number of the feathers and their color. The upper register has covert feathers while the remaining lower registers contain long flight feathers. Both lions are in a supine position and face the viewer with their mouths closed. The overall shape of the owls indicate that they are not from the Fertile Crescent. All of them, the female deity and her companions, face the viewer, at the same time, in dignity. The overall scene is breath-taking, especially if you see it in profile. I spent more than an hour at this relief only! Who was the artist/sculptor who created this wonderful, charming, charismatic, and lovely woman? Did the artist make this work while a nude woman was lying in front of him or her as a model? Did the artist study anatomy? I like Kim Kardashian, but I love this Queen of the Night! If you visit the British Museum, don’t forget to go upstairs (room 56) and meet her majesty! [Ancient History Encyclopedia]. REVIEW: The Burney Relief (also known as the Queen of the Night relief) is a Mesopotamian terracotta plaque in high relief of the Isin-Larsa- or Old-Babylonian period, depicting a winged, nude, goddess-like figure with bird’s talons, flanked by owls, and perched upon two lions. The relief is displayed in the British Museum in London, which has dated it between 1800 and 1750 B.C. It originates from southern Mesopotamia, but the exact find-site is unknown. Apart from its distinctive iconography, the piece is noted for its high relief and relatively large size, which suggest that it was used as a cult relief, making it a very rare survival from the period. However, whether it represents Lilitu, Inanna/Ishtar, or Ereshkigal is under debate. The authenticity of the object has been questioned from its first appearance in the 1930s, but opinion has generally moved in its favor over the subsequent decades. Initially in the possession of a Syrian dealer, who may have acquired the plaque in southern Iraq in 1924, the relief was deposited at the British Museum in London and analyzed by Dr. H.J. Plenderleith in 1933. However, the Museum declined to purchase it in 1935, whereupon the plaque passed to the London antique dealer Sidney Burney; it subsequently became known as the “Burney Relief”. The relief was first brought to public attention with a full-page reproduction in The Illustrated London News, in 1936. From Burney, it passed to the collection of Norman Colville, after whose death it was acquired at auction by the Japanese collector Goro Sakamoto. British authorities, however, denied him an export license. The piece was loaned to the British Museum for display between 1980 and 1991, and in 2003 the relief was purchased by the Museum for the sum of £1,500,000 as part of its 250th anniversary celebrations. The Museum also renamed the plaque the “Queen of the Night Relief”. Since then, the object has toured museums around Britain. Unfortunately, its original provenance remains unknown. The relief was not archaeologically excavated, and thus we have no further information where it came from, or in which context it was discovered. An interpretation of the relief thus relies on stylistic comparisons with other objects for which the date and place of origin have been established, on an analysis of the iconography, and on the interpretation of textual sources from Mesopotamian mythology and religion. Detailed descriptions were published by Henri Frankfort (1936), by Pauline Albenda (2005), and in a monograph by Dominique Collon, curator at the British Museum, where the plaque is now housed. The composition as a whole is unique among works of art from Mesopotamia, even though many elements have interesting counterparts in other images from that time. The relief is a terracotta (fired clay) plaque, 50 by 37 centimeters (20 × 15 inches) large, 2 to 3 centimeters (3/4 to 1 1/4 inches) thick, with the head of the figure projecting 4.5 centimeters (1 3/4 inches) from the surface. To manufacture the relief, clay with small calcareous inclusions was mixed with chaff; visible folds and fissures suggest the material was quite stiff when being worked. The British Museum’s Department of Scientific Research reports, “it would seem likely that the whole plaque was molded” with subsequent modeling of some details and addition of others, such as the rod-and-ring symbols, the tresses of hair and the eyes of the owls. The relief was then burnished and polished, and further details were incised with a pointed tool. Firing burned out the chaff, leaving characteristic voids and the pitted surface we see now; Curtis and Collon believe the surface would have appeared smoothed by ochre paint in antiquity. In its dimensions, the unique plaque is larger than the mass-produced terracotta plaques – popular art or devotional items – of which many were excavated in house ruins of the Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian periods. Overall, the relief is in excellent condition. It was originally received in three pieces and some fragments by the British Museum; after repair, some cracks are still apparent, in particular a triangular piece missing on the right edge, but the main features of the deity and the animals are intact. The figure’s face has damage to its left side, the left side of the nose and the neck region. The headdress has some damage to its front and right hand side, but the overall shape can be inferred from symmetry. Half of the necklace is missing and the symbol of the figure held in her right hand; the owls’ beaks are lost and a piece of a lion’s tail. A comparison of images from 1936 and 2005 shows that some modern damage has been sustained as well: the right hand side of the crown has now lost its top tier, and at the lower left corner a piece of the mountain patterning has chipped off and the owl has lost its right-side toes. However, in all major aspects, the relief has survived intact for more than 3,500 years. Traces of red pigment still remain on the figure’s body that was originally painted red overall. The feathers of her wings and the owls’ feathers were also colored red, alternating with black and white. By Raman spectroscopy the red pigment is identified as red ochre, the black pigment, amorphous carbon (“lamp black”) and the white pigment gypsum. Black pigment is also found on the background of the plaque, the hair and eyebrows, and on the lions’ manes. The pubic triangle and the areola appear accentuated with red pigment but were not separately painted black. The lions’ bodies were painted white. The British Museum curators assume that the horns of the headdress and part of the necklace were originally colored yellow, just as they are on a very similar clay figure from Ur. They surmise that the bracelets and rod-and-ring symbols might also have been painted yellow. However, no traces of yellow pigment now remain on the relief. The nude female figure is realistically sculpted in high-relief. Her eyes, beneath distinct, joined eyebrows, are hollow, presumably to accept some inlaying material – a feature common in stone, alabaster, and bronze sculptures of the time, but not seen in other Mesopotamian clay sculptures. Her full lips are slightly upturned at the corners. She is adorned with a four-tiered headdress of horns, topped by a disk. Her head is framed by two braids of hair, with the bulk of her hair in a bun in the back and two wedge-shaped braids extending onto her breasts. The stylized treatment of her hair could represent a ceremonial wig. She wears a single broad necklace, composed of squares that are structured with horizontal and vertical lines, possibly depicting beads, four to each square. This necklace is virtually identical to the necklace of the god found at Ur, except that the latter’s necklace has three lines to a square. Around both wrists she wears bracelets which appear composed of three rings. Both hands are symmetrically lifted up, palms turned towards the viewer and detailed with visible life-, head- and heart lines, holding two rod-and-ring symbols of which only the one in the left hand is well preserved. Two wings with clearly defined, stylized feathers in three registers extend down from above her shoulders. The feathers in the top register are shown as overlapping scales (coverts), the lower two registers have long, staggered flight feathers that appear drawn with a ruler and end in a convex trailing edge. The feathers have smooth surfaces; no barbs were drawn. The wings are similar but not entirely symmetrical, differing both in the number of the flight feathers and in the details of the coloring scheme. Her wings are spread to a triangular shape but not fully extended. The breasts are full and high, but without separately modeled nipples. Her body has been sculpted with attention to naturalistic detail: the deep navel, structured abdomen, “softly modeled pubic area”, the recurve of the outline of the hips beneath the iliac crest, and the bony structure of the legs with distinct knee caps all suggest “an artistic skill that is almost certainly derived from observed study”. A spur-like protrusion, fold, or tuft extends from her calves just below the knee, which Collon interprets as dewclaws. Below the shin, the figure’s legs change into those of a bird. The bird-feet are detailed, with three long, well-separated toes of approximately equal length. Lines have been scratched into the surface of the ankle and toes to depict the scutes, and all visible toes have prominent talons. Her toes are extended down, without perspective foreshortening; they do not appear to rest upon a ground line and thus give the figure an impression of being dissociated from the background, as if hovering. The two lions have a male mane, patterned with dense, short lines; the manes continue beneath the body. Distinctly patterned tufts of hair grow from the lion’s ears and on their shoulders, emanating from a central disk-shaped whorl. They lie prone, their heads are sculpted with attention to detail, but with a degree of artistic liberty in their form, e.g., regarding their rounded shapes. Both lions look towards the viewer, and both have their mouths closed. The owls shown are recognizable, but not sculpted naturalistically: the shape of the beak, the length of the legs, and details of plumage deviate from those of the owls that are indigenous to the region. Their plumage is colored like the deity’s wings in red, black and white; it is bilaterally similar but not perfectly symmetrical. Both owls have one more feather on the right-hand side of their plumage than on the left-hand side. The legs, feet and talons are red. The group is placed on a pattern of scales, painted black. This is the way mountain ranges were commonly symbolized in Mesopotamian art. Stylistic comparisons place the relief at the earliest into the Isin–Larsa period, or slightly later, to the beginning of the Old Babylonian period. Frankfort especially notes the stylistic similarity with the sculpted head of a male deity found at Ur, which Collon finds to be “so close to the Queen of the Night in quality, workmanship and iconographical details, that it could well have come from the same workshop.” Therefore, Ur is one possible city of origin for the relief, but not the only one. Edith Porada points out the virtual identity in style that the lion’s tufts of hair have with the same detail seen on two fragments of clay plaques excavated at Nippur. And Agnès Spycket reported on a similar necklace on a fragment found in Isin. A creation date at the beginning of the second millennium B.C. places the relief into a region and time in which the political situation was unsteady, marked by the waxing and waning influence of the city states of Isin and Larsa, an invasion by the Elamites, and finally the conquest by Hammurabi in the unification in the Babylonian empire in 1762 B.C. Three to five hundred years earlier, the population for the whole of Mesopotamia was at its all-time high of about 300,000. Elamite invaders then toppled the third Dynasty of Ur and the population declined to about 200,000; it had stabilized at that number at the time the relief was made. Cities like Nippur and Isin would have had on the order of 20,000 inhabitants and Larsa maybe 40,000; Hammurabi’s Babylon grew to 60,000 by 1700 B.C. A well-developed infrastructure and complex division of labor is required to sustain cities of that size. The fabrication of religious imagery might have been done by specialized artisans: large numbers of smaller, devotional plaques have been excavated that were fabricated in molds. Even though the fertile crescent civilizations are considered the oldest in history, at the time the Burney Relief was made other late bronze age civilizations were equally in full bloom. Travel and cultural exchange were not commonplace, but nevertheless possible. To the east, Elam with its capital Susa was in frequent military conflict with Isin, Larsa and later Babylon. Even further, the Indus Valley Civilization was already past its peak, and in China, the Erlitou culture blossomed. To the southwest, Egypt was ruled by the 12th dynasty, further to the west the Minoan civilization, centerd on Crete with the Old Palace in Knossos, dominated the Mediterranean. To the north of Mesopotamia, the Anatolian Hittites were establishing their Old Kingdom over the Hattians; they brought an end to Babylon’s empire with the sack of the city in 1531 B.C. Indeed, Collon mentions this raid as possibly being the reason for the damage to the right-hand side of the relief. The size of the plaque suggests it would have belonged in a shrine, possibly as an object of worship; it was probably set into a mud-brick wall. Such a shrine might have been a dedicated space in a large private home or other house, but not the main focus of worship in one of the cities’ temples, which would have contained representations of gods sculpted in the round. Mesopotamian temples at the time had a rectangular cella often with niches to both sides. According to Thorkild Jacobsen, that shrine could have been located inside a brothel. Compared with how important religious practice was in Mesopotamia, and compared to the number of temples that existed, very few cult figures at all have been preserved. This is certainly not due to a lack of artistic skill: the “Ram in a Thicket” shows how elaborate such sculptures could have been, even 600 to 800 years earlier. It is also not due to a lack of interest in religious sculpture: deities and myths are ubiquitous on cylinder seals and the few steles, kudurrus, and reliefs that have been preserved. Rather, it seems plausible that the main figures of worship in temples and shrines were made of materials so valuable they could not escape looting during the many shifts of power that the region saw. The Burney Relief is comparatively plain, and so survived. In fact, the relief is one of only two existing large, figurative representations from the Old Babylonian period. The other one is the top part of the Code of Hammurabi, which was actually discovered in Elamite Susa, where it had been brought as booty. A static, frontal image is typical of religious images intended for worship. Symmetric compositions are common in Mesopotamian art when the context is not narrative. Many examples have been found on cylinder seals. Three-part arrangements of a god and two other figures are common, but five-part arrangements exist as well. In this respect, the relief follows established conventions. In terms of representation, the deity is sculpted with a naturalistic but “modest” nudity, reminiscent of Egyptian goddess sculptures, which are sculpted with a well-defined navel and pubic region but no details; there, the lower hemline of a dress indicates that some covering is intended, even if it does not conceal. In a typical statue of the genre, Pharao Menkaura and two goddesses, Hathor and Bat are shown in human form and sculpted naturalistically, just as in the Burney Relief; in fact, Hathor has been given the features of Queen Khamerernebty II. Depicting an anthropomorphic god as a naturalistic human is an innovative artistic idea that may well have diffused from Egypt to Mesopotamia, just like a number of concepts of religious rites, architecture, the “banquet plaques”, and other artistic innovations previously. In this respect, the Burney Relief shows a clear departure from the schematic style of the worshiping men and women that were found in temples from periods about 500 years earlier. It is also distinct from the next major style in the region: Assyrian art, with its rigid, detailed representations, mostly of scenes of war and hunting. The extraordinary survival of the figure type, though interpretations and cult context shifted over the intervening centuries, is expressed by the cast terracotta funerary figure of the 1st century B.C., from Myrina on the coast of Mysia in Asia Minor, where it was excavated by the French School at Athens, 1883; the terracotta is conserved in the Musée du Louvre. Similarly sophisticated sculpture would include the Sumerian “Ram in a Thicket”, excavated in the royal cemetery of Ur by Leonard Woolley and dated to about 2600–2400 B.C., and constructed of wood, gold leaf, lapis lazuli and shell. The only other surviving large image from the time: top part of the Code of Hammurabi, circa 1760 B.C. Hammurabi before the sun-god Shamash. This also featured a four-tiered, horned headdress, the rod-and-ring symbol and the mountain-range pattern beneath Shamash’ feet, all of black basalt. Similiar goddess representation occur in Egyptian monuments. For instance, found in the Cairo Museum, the triad of the Egyptian goddess Hathor and the nome goddess Bat leading Pharaoh Menkaura; of fourth dynasty origin, about 2400 B.C. A typical representation of a third millennium B.C. Mesopotamian worshipper, Eshnunna, dated to about 2700 B.C., in alabaster, may be found in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Another Assyrian relief deity representation may be found at the Louvre. Known as a “blessing genie”, the origin the palace of Sargon II, and dated to about 716 B.C. Compared to visual artworks from the same time, the relief fits quite well with its style of representation and its rich iconography. Other similar representations from the same time period include a woman at the Ishtar temple at Mari (between 2500 B.C. and 2400 B.C.), found in the Louvre. The Neo-Sumerian Goddess Bau, also found in the Louvre, the origin Telloh, about 2100 B.C. Also a molded plaque of Ishtar, likewise found in the Louvre, origin early second millennium, Eshnunna. The “Ishtar Vase”, early 2nd millennium B.C., Larsa, also at the Louvre. And finally at the British Museum, a depiction of a woman from an Old Babylonian period temple. Mesopotamian religion recognizes literally thousands of deities, and distinct iconographies have been identified for about a dozen. Less frequently, gods are identified by a written label or dedication; such labels would only have been intended for the literate elites. In creating a religious object, the sculptor was not free to create novel images: the representation of deities, their attributes and context were as much part of the religion as the rituals and the mythology. Indeed, innovation and deviation from an accepted canon could be considered a cultic offense. The large degree of similarity that is found in plaques and seals suggests that detailed iconographies could have been based on famous cult statues; they established the visual tradition for such derivative works but have now been lost. It appears, though, that the Burney Relief was the product of such a tradition, not its source, since its composition is unique. The frontal presentation of the deity is appropriate for a plaque of worship, since it is not just a “pictorial reference to a god” but “a symbol of his presence”. Since the relief is the only existing plaque intended for worship, we do not know whether this is generally true. But this particular depiction of a goddess represents a specific motif: a nude goddess with wings and bird’s feet. Similar images have been found on a number of plaques, on a vase from Larsa (described above), and on at least one cylinder seal. They are all from approximately the same time period. In all instances but one, the frontal view, nudity, wings, and the horned crown are features that occur together; thus, these images are iconographically linked in their representation of a particular goddess. Moreover, examples of this motif are the only existing examples of a nude god or goddess; all other representations of gods are clothed. The bird’s feet have not always been well preserved, but there are no counter-examples of a nude, winged goddess with human feet. The horned crown, usually four-tiered, is the most general symbol of a deity in Mesopotamian art. Male and female gods alike wear it. In some instances, “lesser” gods wear crowns with only one pair of horns, but the number of horns is not generally a symbol of “rank” or importance. The form we see here is a style popular in Neo-Sumerian times and later; earlier representations show horns projecting out from a conical headpiece. Winged gods, other mythological creatures, and birds are frequently depicted on cylinder seals and steles from the 3rd millennium all the way to the Assyrians. Both two-winged and four-winged figures are known and the wings are most often extended to the side. Spread wings are part of one type of representation for Ishtar. However, the specific depiction of the hanging wings of the nude goddess may have evolved from what was originally a cape. The rod and ring symbol may depict the measuring tools of a builder or architect or a token representation of these tools. It is frequently depicted on cylinder seals and steles, where it is always held by a god, usually either Shamash, Ishtar, and in later Babylonian images also Marduk. The symbol was also often extended to a king. Lions are chiefly associated with Ishtar or with the male gods Shamash or Ningirsu. In Mesopotamian art, lions are nearly always depicted with open jaws. H. Frankfort suggests that The Burney Relief shows a modification of the normal canon that is due to the fact that the lions are turned towards the worshipper: the lions might appear inappropriately threatening if their mouths were open. No other examples of owls in an iconographic context exist in Mesopotamian art, nor are there textual references that directly associate owls with a particular god or goddess. A god standing on or seated on a pattern of scales is a typical scenery for the depiction of a theophany. It is associated with gods who have some connection with mountains but not restricted to any one deity in particular. The figure has initially been identified as a depiction of Ishtar (Inanna), but almost immediately other arguments have been put forward. The identification of the relief as depicting “Lilith” has become a staple of popular writing on that subject. Raphael Patai believes the relief to be the only extant depiction of a Sumerian female demon called lilitu and thus to define lilitu’s iconography. Citations regarding this assertion lead back to Henri Frankfort (in 1936). Frankfort himself based his interpretation of the deity as the demon Lilith on the presence of wings, the birds’ feet and the representation of owls. He cites the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh as a source that such “creatures are inhabitants of the land of the dead”. In that text Enkidu’s appearance is partially changed to that of a feathered being, and he is led to the nether world where creatures dwell that are “birdlike, wearing a feather garment”. This passage reflects the Sumerians’ belief in the nether world, and Frankfort cites evidence that Nergal, the ruler of the underworld, is depicted with bird’s feet and wrapped in a feathered gown. However Frankfort did not himself make the identification of the figure with Lilith; rather he cites Emil Kraeling (1937) instead. Kraeling believes that the figure “is a superhuman being of a lower order”; he does not explain exactly why. He then goes on to state “Wings…regularly suggest a demon associated with the wind” and “owls may well indicate the nocturnal habits of this female demon”. He excludes Lamashtu and Pazuzu as candidate demons and states: “Perhaps we have here a third representation of a demon. If so, it must be Lilîtu…the demon of an evil wind”, named ki-sikil-lil-la (literally “wind-maiden” or “phantom-maiden”, not “beautiful maiden”, as Kraeling asserts. This ki-sikil-lil is an antagonist of Inanna (Ishtar) in a brief episode of the epic of Gilgamesh, which is cited by both Kraeling and Frankfort as further evidence for the identification as Lilith, though this appendix too is now disputed. In this episode, Inanna’s holy Huluppu tree is invaded by malevolent spirits. Frankfort quotes a preliminary translation by Gadd (1933): “in the midst Lilith had built a house, the shrieking maid, the joyful, the bright queen of Heaven”. However modern translations have instead: “In its trunk, the phantom maid built herself a dwelling, the maid who laughs with a joyful heart. But holy Inanna cried.” The earlier translation implies an association of the demon Lilith with a shrieking owl and at the same time asserts her god-like nature; the modern translation supports neither of these attributes. In fact, Cyril J. Gadd (1933), the first translator, writes: “ardat lili (kisikil-lil) is never associated with owls in Babylonian mythology” and “the Jewish traditions concerning Lilith in this form seem to be late and of no great authority”. This single line of evidence was taken as virtual proof of the identification of the Burney Relief with “Lilith” may have been motivated by later associations of “Lilith” in later Jewish sources. The association of Lilith with owls in later Jewish literature such as the Songs of the Sage (1st century B.C.) and Babylonian Talmud (5th century A.D.) is derived from a reference to a liliyth among a list of wilderness birds and animals in Isaiah (7th century B.C.), though some scholars, such as Blair (2009) consider the pre-Talmudic Isaiah reference to be non-supernatural, and this is reflected in some modern Bible translations: Isaiah 34:13 “Thorns shall grow over its strongholds, nettles and thistles in its fortresses. It shall be the haunt of jackals, an abode for ostriches. And wild animals shall meet with hyenas; the wild goat shall cry to his fellow; indeed, there the night bird (lilit or lilith) settles and finds for herself a resting place. There the owl nests and lays and hatches and gathers her young in her shadow; indeed, there the hawks are gathered, each one with her mate.” Today, the identification of the Burney Relief with Lilith is questioned, and the figure is now generally identified as the goddess of love and war. Fifty years later, Thorkild Jacobsen substantially revised this interpretation and identified the figure as Inanna (Akkadian: Ishtar) in an analysis that is primarily based on textual evidence. According to Jacobsen: “The hypothesis that this tablet was created for worship makes it unlikely that a demon was depicted. Demons had no cult in Mesopotamian religious practice since demons ‘know no food, know no drink, eat no flour offering and drink no libation.’ Therefore, ‘no relationship of giving and taking could be established with them'”. The horned crown is a symbol of divinity, and the fact that it is four-tiered suggests one of the principal gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon. Inanna was the only goddess that was associated with lions, for example a hymn by En-hedu-ana specifically mentions “Inanna, seated on crossed (or harnessed) lions”. The goddess is depicted standing on mountains. According to text sources, Inanna’s home was on Kur-mùsh, the mountain crests. Iconographically, other gods were depicted on mountain scales as well, but there are examples in which Inanna is shown on a mountain pattern and another god is not, i.e. the pattern was indeed sometimes used to identify Inanna. The rod-and-ring symbol, her necklace and her wig are all attributes that are explicitly referred to in the myth of Inanna’s descent into the nether world. Jacobsen quotes textual evidence that the Akkadian word eššebu (owl) corresponds to the Sumerian word ninna, and that the Sumerian Dnin-ninna (Divine lady ninna) corresponds to the Akkadian Ishtar. The Sumerian ninna can also be translated as the Akkadian kilili, which is also a name or epithet for Ishtar. Inanna/Ishtar as harlot or goddess of harlots was a well known theme in Mesopotamian mythology and in one text, Inanna is called kar-kid (harlot) and ab-ba-[šú]-šú, which in Akkadian would be rendered kilili. Thus there appears to be a cluster of metaphors linking prostitute and owl and the goddess Inanna/Ishtar; this could match the most enigmatic component of the relief to a well known aspect of Ishtar. Jacobsen concludes that this link would be sufficient to explain talons and wings, and adds that nudity could indicate the relief was originally the house-altar of a bordello. In contrast, the British Museum does acknowledge the possibility that the relief depicts either Lilith or Ishtar, but prefers a third identification: Ishtar’s antagonist and sister Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld.] This interpretation is based on the fact that the wings are not outspread and that the background of the relief was originally painted black. If this were the correct identification, it would make the relief (and by implication the smaller plaques of nude, winged goddesses) the only known figurative representations of Ereshkigal. Edith Porada, the first to propose this identification, associates hanging wings with demons and then states: “If the suggested provenience of the Burney Relief at Nippur proves to be correct, the imposing demonic figure depicted on it may have to be identified with the female ruler of the dead or with some other major figure of the Old Babylonian pantheon which was occasionally associated with death.” No further supporting evidence was given by Porada, but another analysis published in 2002 comes to the same conclusion. E. von der Osten-Sacken describes evidence for a weakly developed but nevertheless existing cult for Ereshkigal; she cites aspects of similarity between the goddesses Ishtar and Ereshkigal from textual sources – for example they are called “sisters” in the myth of “Inanna’s descent into the nether world” – and she finally explains the unique doubled rod-and-ring symbol in the following way: “Ereshkigal would be shown here at the peak of her power, when she had taken the divine symbols from her sister and perhaps also her identifying lions”. The 1936 London Illustrated News feature had “no doubt of the authenticity” of the object which had “been subjected to exhaustive chemical examination” and showed traces of bitumen “dried out in a way which is only possible in the course of many centuries”. But stylistic doubts were published only a few months later by D. Opitz who noted the “absolutely unique” nature of the owls with no comparables in all of Babylonian figurative artifacts. In a back-to-back article, E. Douglas Van Buren examined examples of Sumerian art, which had been excavated and provenanced and she presented examples: Ishtar with two lions, the Louvre plaque of a nude, bird-footed goddess standing on two Ibexes and similar plaques, and even a small haematite owl, although the owl is an isolated piece and not in an iconographical context. A year later Frankfort acknowledged Van Buren’s examples, added some of his own and concluded “that the relief is genuine”. Opitz (1937) concurred with this opinion, but reasserted that the iconography is not consistent with other examples, especially regarding the rod-and-ring symbol. These symbols were the focus of a communication by Pauline Albenda (1970) who again questioned the relief’s authenticity. Subsequently the British Museum performed thermoluminescence dating which was consistent with the relief being fired in antiquity; but the method is imprecise when samples of the surrounding soil are not available for estimation of background radiation levels. A rebuttal to Albenda by Curtis and Collon (1996) published the scientific analysis; the British Museum was sufficiently convinced of the relief to purchase it in 2003. The discourse continued however: in her extensive reanalysis of stylistic features, Albenda once again called the relief “a pastiche of artistic features” and “continue[d] to be unconvinced of its antiquity”. Her arguments were rebutted in a rejoinder by Collon (2007), noting in particular that the whole relief was created in one unit, i.e. there is no possibility that a modern figure or parts of one might have been added to an antique background. Collon also reviewed the iconographic links to provenanced pieces. In concluding Collon states: “[Edith Porada] believed that, with time, a forgery would look worse and worse, whereas a genuine object would grow better and better…Over the years [the Queen of the Night] has indeed grown better and better, and more and more interesting. For me she is a real work of art of the Old Babylonian period.” In 2008/9 the relief was included in exhibitions on Babylon at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the Louvre in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. [Wikipedia]. REVIEW: Ishtar was the Mesopotamian goddess of love, beauty, sex, desire, fertility, war, combat, and political power, the East Semitic (Akkadian, Assyrian, and Babylonian) counterpart to the Sumerian Inanna, and a cognate of the Northwest Semitic goddess Astarte and the Armenian goddess Astghik. Ishtar was an important deity in Mesopotamian religion from around 3500 B.C., until its gradual decline between the 1st and 5th centuries CE with the spread of Christianity. Ishtar’s primary symbols were the lion and the eight-pointed star of Ishtar. She was associated with the planet Venus and subsumed many important aspects of her character and her cult from the earlier Sumerian goddess Inanna. Ishtar’s most famous myth is the story of her descent into the underworld, which is largely based on an older, more elaborate Sumerian version involving Inanna. In the standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar is portrayed as a spoiled and hot-headed femme fatale who demands Gilgamesh to become her consort. When he refuses, she unleashes the Bull of Heaven, resulting in the death of Enkidu. This stands in sharp contrast with Inanna’s radically different portrayal in the earlier Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld. Ishtar also appears in the Hittite creation myth and in the Neo-Assyrian Birth Legend of Sargon. Although various publications have claimed that Ishtar’s name is the root behind the modern English word Easter, this has been rejected by reputable scholars, and such etymologies are not listed in standard reference works. Ishtar is a Semitic name of uncertain etymology, possibly derived from a Semitic term meaning “to irrigate”. George A. Barton, an early scholar on the subject, suggests that the name stems from “irrigating ditch” and “that which is irrigated by water alone”, therefore meaning “she who waters”, or “is watered” or “the self-waterer”.Regardless of which interpretation is correct, the name seems to derive from irrigation and agricultural fertility. The name Ishtar occurs as an element in personal names from both the pre-Sargonic and post-Sargonic eras in Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia. A few scholars believe that Ishtar may have originated as a female form of the god Attar, who is mentioned in inscriptions from Ugarit and southern Arabia. The morning star may have been conceived as a male deity who presided over the arts of war and the evening star may have been conceived as a female deity wh

Frequently Asked Questions About Babylonian Goddess Ishtar Lilitu Bible’s Lilith Mesopotamia 1800BC Shrine Plaque in My Website

istamarvel.com is the best online shopping platform where you can buy Babylonian Goddess Ishtar Lilitu Bible’s Lilith Mesopotamia 1800BC Shrine Plaque from renowned brand(s). istamarvel.com delivers the most unique and largest selection of products from across the world especially from the US, UK and India at best prices and the fastest delivery time.

What are the best-selling Babylonian Goddess Ishtar Lilitu Bible’s Lilith Mesopotamia 1800BC Shrine Plaque on istamarvel.com?

istamarvel.com helps you to shop online and delivers Evisu to your doorstep. The best-selling Evisu on istamarvel.com are: EVISU Jeans cotton blue Used Denim Jeans EVISU Lot2000 JEANS Selvedge DENIM JAPAN W25 Denim Jeans EVISU Blue JEANS JAPAN DENIM W27.5 Rare Skull Embroidered Evisu Jeans Evisu Jeans 34 Evisu Women’s Denim Jeans Pants Seagull Cotton Blue Pink Size 24 Casual Mens Evisu Designer Jeans W32 L32 Denim Y2K Skater Medium Blue Yellow Logo Evisu Embroidery Tiger Denim Jean Size 42 Kuhl Men’s Easy Rydr Hiking Pants Size 38 x 32 Dark Brown EVISU Multi Pocket Denim Pants Indigo Cotton 34 x 34 PALACE EVISU DENIM CAMO DENIM JEANS EVISU 2001 No.2 Jeans Denim Damaged JAPAN W28 Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (29″) Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS Red Selvedge DENIM Leather Patch Japan W:27 Inseam:28 Vintage Evisu Pockets Logo Cotton Denim Jeans Blue Men’s Size 32 Denim Jeans EVISU × McDonald’s Collabo JEANS Selvedge DENIM W:27 Inseam:35 NEW Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS 2000T Selvedge DENIM Pants Panda Seagull W:27 Inseam:27 Voi Jeans Japanese Raw Denim Avant Garde Y2K Baggy Vintage 90S Evisu Vibe -30×28 Men size M Evisu Old No.2 Sea Bream Fishing Leather Patch Denim Jeans Vintage JP Evisu Men’s Super Slim Straight Leg Gray Jeans – Size 30×30.5 Authentic Vintage Diacock Evisu Jeans (29″) Vintage Y2K Rocawear Baggy Hip Hop Skater Grunge Jeans VTG Mens Size 36 Dark Denim Jeans EVISU YAMANE JEANS 1926 Selvedge DENIM TIGER DRAGON W:30 Inseam:33 Authentic Vintage Evisu jeans (27″) Vintage Evisu lot:0005 selvedge jeans Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS Lot2000 No2 Selvedge DENIM Pants Size W:28 Inseam:33 Jinzu Jeans Mens 32×32 Blue Denim Hip Hop Y2K Goth Embroidered Skate EVISU offset Jeans denim indigo 33 Used EBISU Seagull White Denim Pants Golf Pants Discontinued Product EVISU Denim pants straight Jeans size 32 casual Men’s bottoms lot2517 Vintage Wrangler Jeans Men 42×32 Straight Camo Real Tree Double Knee Y2K Hunting evisu jeans size 34 EVISU Selvedge Embroidered Denim Jeans Evisu Men’s Jeans slim fit Raw denim w Back pockets design sample size 32×32 575 Evisu Jeans Men’s custom made Japanese Vintage Sanforized denim size 32 NEW Evisu Jeans Distressed Pants Blue Jeans Evisu Size 32L EVISU Black Seagull Dark Blue NO.2 W32 2001 Made in Japan Red ear From JAPAN◎ Wrangler Pro Gear Realtree Hunting Camo Pants Jeans Men’s 40×30 Camouflage EVISU jeans 2501 size 34 Evisu Indigo Genes Mens Denim Jeans Size 32 x 34 Blue Selvedge Lot.0001 STF No1 Vintage Evisu Genes EV Jeans Denim Size 30 Denim Jeans EVISU 2504XX JEANS Selvedge DENIM Leather Patch Japan W:25 Inseam:34 EVISU KOI CARP SELVEDGE SHORTS JHORT JEANS sz36 SKATE/VINTAGE/90S/DC/KALIS/SHOES Evisu Vintage Selvedge Diacock Big M Navy/ Red Japanese Denim Jeans Size 32 Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS Many Pockets DENIM Pants Japan Size 44 Evisu Blue Denim Straight Jeans Size 34 EVISU KURU SLIM STRETCH JEANS sz31 SKATE/90S/JAPAN/DENIM Denim Jeans EVISU Jeans Pink Seagull DENIM Pants Japan W:26 Inseam:28 Vintage Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (30″) Womens Evisu Custom Made 10 oz Gull Skinny Blue Jeans Size W26 L32 Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (32″) Mens Evisu Jeans Selvedge Denim EU ED Ninja Jeans Made in Italy W 30 L 31 Evisu Jeans Mens 31/34″ Japanese Selvedge Dark Navy Blue Custom No.3 Lot 2000 Evisu Japanese Denim Indigo Jeans NO.1 32 EVISU Straight Jeans denim indigo 26 Used Jaded London PANTS JEANS colossus fit big by rick owens evisu balenciaga empyre *Rare* 2000s Evisu Jeans – Japanese Release -Waist 36Inch x Lenght 32Inch Evisu selvedge jeans denim pants evisu Vintage Denim jeans Sz38 Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS × Hello Kitty Collabo DENIM Pants Kid’s size 4(160cm) Evisu Jeans N 1 Size-40 Authentic Vintage Evisu x McDonald’s Jeans (25″) Yamane by Evisu Man Jeans Size-30×35 Denim Jeans EVISU DONNA JEANS Ladies DENIM Stitched Seagull Size W:24 Inseam:31 Mens EVISU Denim Jeans Size 36×34 Big Logo 2017 Evisu Japanese Calligraphy Denim Jeans Vintage Evis Size 29 2504XX deadstock Made in Japan No.2 Evisu denim jeans Fish Evisu Skinny Jeans Patch Paint Splatter 26 X 27 EVISU X Puma Collaboration Jeans Women ACTL 31×32 Blue Straight Leg Denim Adult Evisu Embroidered Vintage Jeans 34 VTG Evisu Denim Genes JAPON Indico Daicock With Kamon Denim Sz. 42 5 Button 🔥 mens evisu jeans 32/32 – Read Description Denim Jeans EVISU × PUMA Collabo Short Pants Ladies DENIM Pants W:30 Length:12 Denim Jeans EVISU JEANS × Hello Kitty Collabo DENIM Pants Japan W:29 Inseam:28 Authentic Vintage Diacock Evisu Jeans (30″) EVISU Denim Pants Blue(Denim) 29(Approx. S) 2200498988011 Evisu Heritage Indigo Genes Rare Men Seagull Logo Jeans Size 38 (Actual 36×30.5) Evisu Japan denim Jeans Lot 0001 Selvedge 30-31 Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (28″) Denim Jeans EVISU × PUMA Collabo JEANS Straight DENIM Pants W:27 Inseam:30 Vintage Evisu Jeans Women’s 32×33 Blue Denim Low Rise Bell Bottom Flared Italy BUNDLE-Evisu, MM6, Helmut Lang, Vintage Miss Sixty, Bebe bottoms EVISU x Hello Kitty Collaboration Denim Jeans Pants Selvedge No2 2001 30×34 NEW Evisu Jeans Originals From 2000s Size 30 Waist A.P.C. Jeans 30 EVISU For Maniac Graphic Print Backpocket Skinny Crop Fray Jeans Size: 64/26 Versace Jeans Couture Ittierre Mens Straight Leg Pants Size 34 Evisu Genes Denim Vintage Jeans Mens 38 Solid Blue Flat Front EVISU VINTAGE JEANS 34 Evisu Denim Jeans Japan Regular Straight Fit Blue Mens W28 L30 Vintage Evisu Puma Japanese Denim Jeans 34 32 Y2K USA EVISU DARUMA DOUBLE DAICOCK CROPPED FIT JEANS #2027! Evisu Heritage Denim Jeans – Size 38 Very Rare Vintage Evisu Genes Paris Edition Denim Jeans Sz36 Evisu Puma Jeans Black Denim True Love Never Dies Straight Size 31W 28L Vintage Evisu Ladies Stripped jeans very rare size 29 x 32 Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (32″) Authentic Vintage Evisu Jeans (32″) EVISU jeans No.2 Lot.2000 Red thread W36 Vintage denim men’s Made in Japan Evisu Jeans 18aw men’s slim fit straight cheeky dharma embroidery Red size M Mens Pullover Fleece Hoodie